Seagrass

Seagrass or rimurēhia, (Zostera muelleri), is a perennial flowering marine plant that, despite its grass-like leaves, is not a grass at all, being more closely related to arum lilies. Most seagrass species complete their entire life cycle under water and Z. muelleri is no different.

It has pollen adapted to dispersion by water and flowers that are reduced to a small spike for catching the pollen. It grows by budding stems and leaves from a creeping root system (rhizome) and by this means forms large spreading mats of interconnected plants.

Zostera muelleri is a southern hemisphere temperate species of seagrass native to the coasts of South Australia, Victoria, Tasmania and New Zealand and sometimes referred to as eelgrass or garweed. It is the only species of Zostera in New Zealand but one of many different species of seagrass that occur throughout temperate and subtropical zones of the world.

In 2012 Pāuatahanui Inlet was estimated to have the highest seagrass coverage of any harbour in the lower North Island.

Kingdom: Plantae

Clade: Tracheophytes

Clade: Angiosperms

Clade: Monocotyledon

Order: Alismatales

Family: Zosteraceae

Genus: Zostera

Species: Z. muelleri

Taxonomy

Seagrass is not a grass, nor is it a seaweed, although it grows on tidal sand flats, channel banks and shallow subtidal sandy areas in estuaries throughout the country. Instead seagrass is a monocotyledonous marine flowering plant belonging to the plant family Zosteraceae.

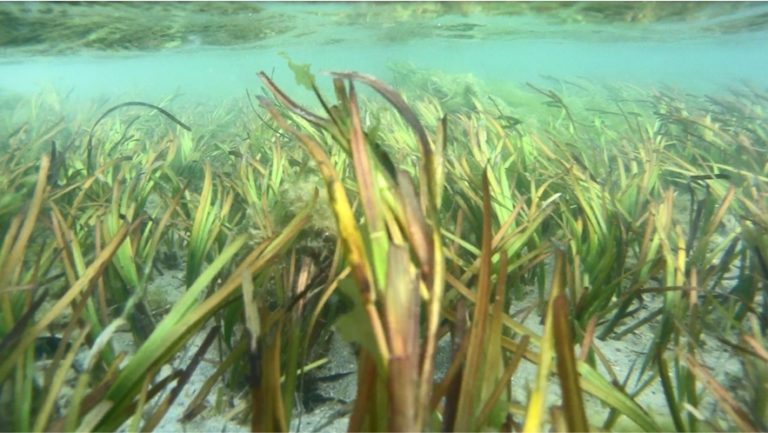

Where it is abundant it forms a dense cover on sand flats that can appropriately be called a seagrass meadow. These meadows serve as a feeding ground for wading birds and aquatic animals as well as a breeding ground for several marine species.

Seagrass v eelgrass: In the past the name ‘eelgrass’ was applied to Zostera sp. meaning there was no distinction between these marine plants and the largely aquatic freshwater species of the same family but in the genus Vallisneria. In more recent times however the term ‘eelgrass’ has been dropped in favour of ‘seagrass’, leaving the Vallisneria species alone to be called ‘eelgrass’ .

The importance of seagrass

Seagrasses are a very important group of plants that make a vital contribution to the marine environment and in particular the ecology of the Inlet. Their role is a multipurpose one:

- Seagrass is a first order blue carbon absorber, with high uptake of CO₂ from the water and atmosphere. In this role seagrass meadows exceed the efficiency of tropical forests and therefore are even more important in regulating the climatic balance of carbon than any other plant community on the planet.

- Seagrass is a key primary producer of complex organic molecules, combining atmospheric and aqueous CO₂ through the process of photosynthesis, drawing energy from the sun, and releasing oxygen back into the atmosphere. Through this process the plant contributes significantly to the nutrient cycle with the uptake of nitrogen, phosporus and sulphur minerals incorporated into organic compounds that are eventually reused by other plants and animals. Seagrass meadows are one of the most productive habitats of all in this process.

- By absorbing nutrients from the water and seabed sediments seagrass plants help to offset the damaging effects of excess nutrient flow from the surrounding catchment.

- The masses of leaf blades impede the movement of water currents, allowing small suspended particles to settle out on the leaves and the seabed, while the masses of interconnecting rhizomes and roots bind the material into the seafloor sediments. This has the effect of improving water clarity and enhancing the environment for other aquatic plants such as algae on the sea bed and diatoms in the plankton.

- The trapping of inorganic sediments provides a habitat for surface and subsurface for invertebrates. Much of the suspended material is organic debris coming from the death and decay of plants in the saltmarsh at the head of the Inlet and this is food for numerous species of animals from microscopic crustaceans to larger crustacea, worms, shellfish and fishes.

- When covered at high tide the leaves, lying flat when exposed, become upstanding and form a ‘forest’ that gives shelter to many small animals. In this way the meadows become nurseries for larval and juvenile stages of several fish species.

- The small animals that live in the seagrass beds are an important food source for fish (e.g. yellow-eyed mullet, stargazer, and juveniles of flatfish, snapper, trevally, garfish, spotty) and wading birds (e.g. oystercatcher, pied stilt, spoonbill).

- Seagrass itself is a major food species for black swans.

Seagrass in the Inlet is under threat

- Excessive fine sediment coming in from the catchment can smother the seagrass, blocking out light. This is detrimental to the survival of the plants causing them to die off.

- Very high levels of plant nutrients, mainly nitrogen and phosphorus from agricultural sources, can encourage the growth of a parasitic plant protist called Labyrinthula zosterae that causes ‘wasting disease’ of seagrass. This displays firstly as a discolouration of the leaves followed by the appearance of black or brown splotches.

- Human activities on the foreshore can damage the habitat – the seagrass can be trampled by vehicles or boats being dragged over the shore, and even by horses being exercised.

Dense seagrass meadows were once abundant in the Inlet but a recent survey by NIWA shows that about 40% of its seagrass cover has been lost since 1980, mostly from the eastern end. This decline correlates in time with the doubling of nitrate concentration in the sea water in this area since the 1970s, possibly coupled with increased siltation. NIWA makes the obvious recommendation that these probable causes need to be eliminated before successful restoration is likely, but does suggest that some transplantation experiments could be done now to assess the current situation.