Human History

Early Polynesians

Early Polynesians were probably visiting the Pāuatahanui Inlet by about 1200 AD. The forest birds of the area and the fish and shellfish of the Inlet would have been attractive to their way of life and would have remained so for many centuries. It is probable that from the earliest times the Inlet itself was just one of the many ecological zones which the people of a major settlement at Paremata made use of, although there are traces of occupied sites (15th/16th Century) at Motukaraka Point and at Ration Point. Māori tradition records occupation by Ngāi Tara at this time followed by Ngāti Kahungunu and Ngāti Ira, who were in turn displaced by the Ngāti Toa invasion of the Kapiti/Wellington area in about 1820 led by Te Rauparaha.

Ngāti Toa were well positioned to trade with the whalers who were establishing small shore stations at Kapiti and Mana Island and at Paremata, Porirua and near Titahi Bay in the early 1830s. Pigs and potatoes were traded for weaponry, blankets, tools, tobacco and other desirable goods. Dressed flax became an important export and it is likely a portion of it came from swamps around the Inlet. By the 1830s there were Pakeha flax traders and men who had married Ngāti Toa women living in the Porirua area.

Arrival of the British

British colonization began with the arrival of Captain William Wakefield in 1839 to buy land for the New Zealand Company which was about to send settlers in four ships to Port Nicholson, the historical name for Te-Whanganui-a-Tara, Wellington Harbour. Pāuatahanui, with the land surrounding the Inlet, was one of the purchases made from Te Rauparaha and a ‘Village of Porirua’ was planned for Motukaraka Point in the series of 100-acre surveyed blocks surrounding Porirua Harbour.

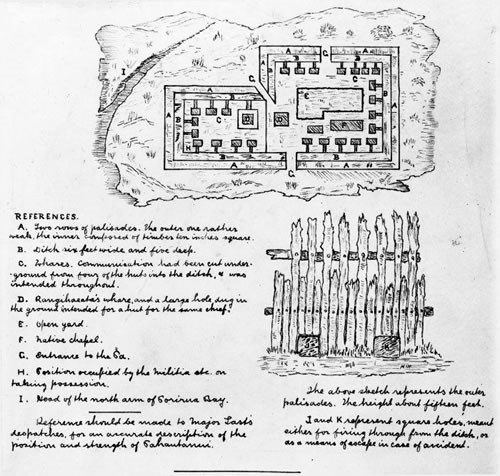

Disputes over the land purchases simmered on while the Treaty of Waitangi was being presented for signature to Ngāti Toa chiefs in 1840 and in the next few years there were several conflicts between parties of Ngāti Toa and surveyors or would-be farmers and timber millers. Tension between Ngāti Toa and Wellington settlers who were expanding into the Hutt Valley led to the stationing of British troops there and the forming of a settler militia. By this stage the principal opponent of settler expansion, both in the Hutt Valley and in the Porirua district, was Te Rauparaha’s vigorous and able nephew, Te Rangihaeata. Te Rangihaeata moved from Mana Island to a pa at Motukaraka in 1845.

Te Rangihaeata

Te Rangihaeata was born in 1780 at Kawhia in the Waikato. He belonged to Ngāti Toa, a fierce tribe who fought their way down the North Island trying to find somewhere to establish themselves. On their way south, they attacked tribes as they passed through Taranaki, Whanganui and Horowhenua. During this time Te Rangihaeata married one of the women whom he had taken prisoner. The tribe migrated down to the Kapiti coast and finally arrived at Porirua where Te Rangihaeata built several pa.

Ngāti Ira had lived in and around Porirua and the Inlet since about 1600 but the Ngāti Toa warriors drove them away so they went over to the Wairarapa and resettled there.

Te Rangihaeata had very early contact and connections with Pakeha. By 1832 he was already trading with the European whalers who were working from Mana Island. When the New Zealand Company, represented by Colonel Wakefield, started buying up land so the English settlers could establish farms, Te Rangihaeata took part in the negotiations.

At first he was very happy to engage with Pakeha because he liked the trade and the exciting new goods they brought with them. In January of 1840 Captain William Hobson, under the title lieutenant-governor, arrived at the Bay of Islands charged with establishing British sovereignty. A treaty was quickly drafted in English, and translated into Māori, and on 6 February signed by about 40 Māori Chiefs at Waitangi. In the days that followed it was circulated around the whole of New Zealand and Te Rauparaha was one of the additional signatories to the document. At the time there was no indication of the problems the treaty would create in later years.

Soon, however, settlers in the Nelson region, led by Arthur Wakefield, wanted to expand into the Wairau Valley without agreement from the tribe. This was Ngāti Toa land and both Te Rangihaeata and Te Rauparaha railed against incursion. They took a party of warriors across Cook Strait and threated the surveyors, warning that they would burn their camp if it continued. The warning was ignored and the tribe carried out their threat. Charge with arson, Te Rangihaeata attempted to negotiate, but tempers flared and shots were fired one of which unfortunately killed Te Rangihaeata’s wife. Wakefield’s party then surrendered and were taken prisoner. In retaliation Te Rangihaeata took revenge (or utu according to Māori Custom) killing many of Wakefield’s men and some of his own. One of the dead prisoners was Colonel Wakefield himself. The battle is known in the history books as the Wairau Massacre.

The governor of New Zealand, Governor George Grey, became very concerned that Te Rangihaeata was getting too powerful and dangerous so he decided to try and restrain him. He sent troops to capture him, but the chief had built a strong pa at the head of the Pāuatahanui Inlet on the hill where St Albans church stands today.

At that time, before the 1855 earthquake, it is thought that the sea came right up to the bottom of the hill. Certainly the water was deep enough for ships’ boats, armed with a small cannon, to sail up the Inlet and land troops near the village. Other troops came over from the Hutt Valley to join the attack on the pa.

Te Rangihaeata knew that he had to get the children and old people away to protect them from the Government forces. By the time the soldiers arrived, he had already abandoned the pa and taken the tribe into the area known today as Battle Hill, not far up the Paekakariki Hill road. He took them to the top of the hill where he could easily see the approaching British soldiers. The British did not have enough food with them and were weighed down by their uniforms and guns, so after four days they had to retreat. Te Rangihaeata led his people over the hill to Poroutawhao, north of Levin. He lived there for the rest of his life and died in 1855 from pneumonia, caught when he lay in a stream to try to get rid of a fever caused by measles.

He is remembered as one of the fiercest fighting chiefs, who strongly resisted the displacement of his people and their culture.